44 | Close to the Bayou by Dimitri Staszewski

Hello all,

Welcome to 2024’s first edition of The Practice. Thanks for being here.

To begin this year, this newsletter is returning to where it started and is incorporating a Q&A. This edition will discuss Dimitri Staszewski’s, a friend and colleague, latest photo book.

We will dive into the motivation for personal projects, what he discovered in the process, and the details of moving an idea into something tangible to share with others.

Before we dive into the Q&A, I wanted to highlight a piece by Alicia Kennedy that I read on New Year’s Day. It was an impactful article to read at the beginning of the new year.

Ok, now onto the conversation with Staszewski and the project “Close to the Bayou.”

Q&A with Dimitri

This conversation was lightly edited for clarity.

Evan: Dimitri, can you provide the framework for this project? A background on the artist you were photographing? How has the project morphed over the years?

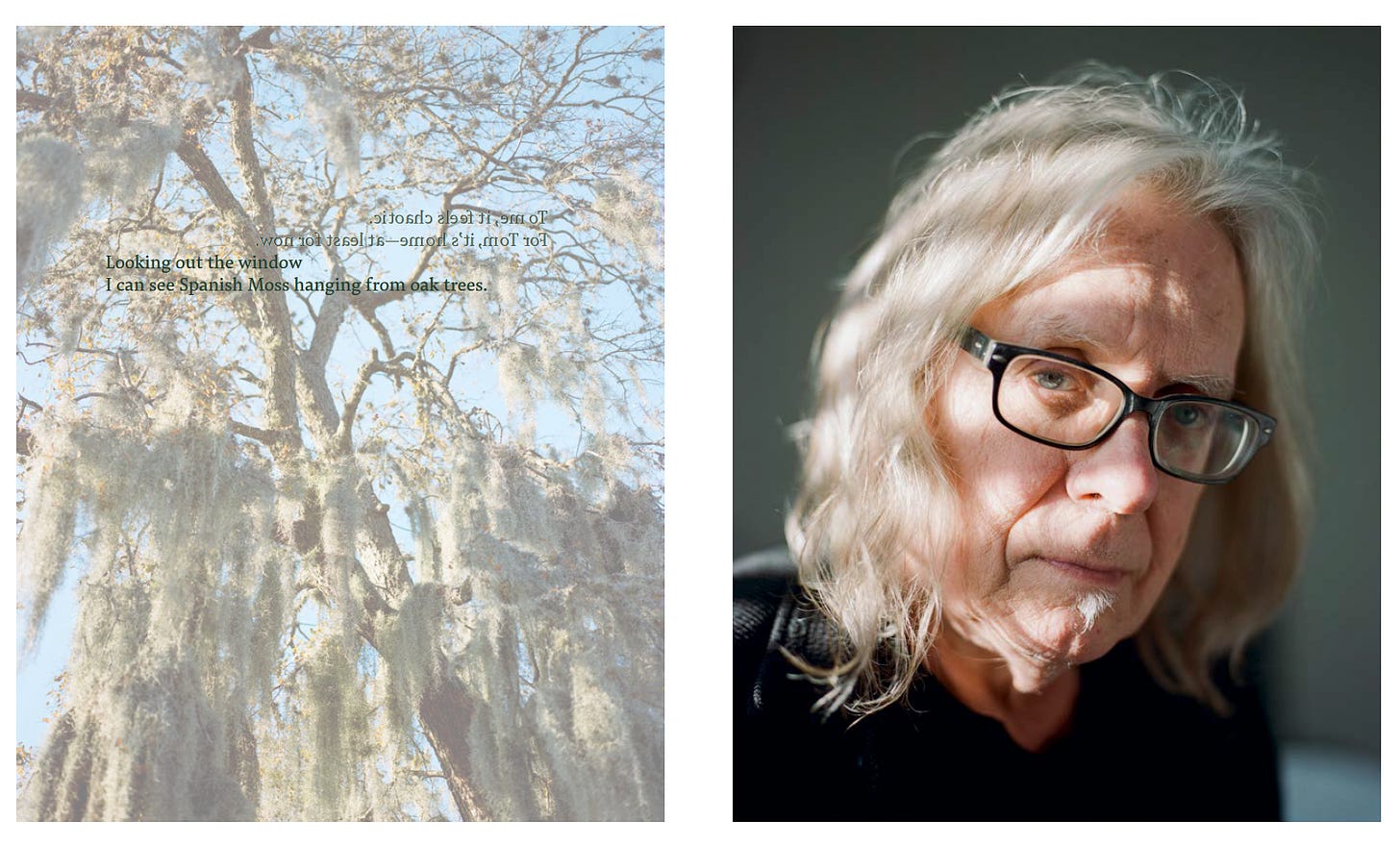

Dimitri: The project began in January 2021 as Thomas Mann, a close friend, artistic mentor, and uncle figure in my life, began treatment for prostate cancer at MD Anderson in Houston.

Tom, as all his close friends call him, is a longtime friend of my dad. They are both jewelers and did craft shows for years together before I was born. Until I graduated high school, I wanted to become a jeweler like my dad. As I was growing up, Tom was an important figure in my life as he served as a very different example of what being an artist could look like compared to my dad. My father is a very disciplined German-trained master goldsmith, while Tom is this boisterous, at times chaotic, figure who lives in New Orleans and is always brimming with inspiration.

Tom had asked me during the summer of 2020 to set aside some time to support him during his treatment. The only non-negotiable need was a ride from the hospital back to where he’d be staying as he’d be coming off anesthesia from the surgery that would mark the beginning of his treatment. He rented a two-bedroom home with a garage during his three-month treatment period. I helped him turn the garage into a jewelry studio where he’d create work throughout his treatment. I asked why he was setting up two benches. He explained, “That one’s for you.”

I ended up committing to supporting Tom through his experience but also to the experience more broadly. I would drive from Austin to Houston each Friday to be with Tom for three months. I’d help clean the house, we’d cook dinner together, and then talk late into the night. On Saturdays, we’d make jewelry together all day, cook dinner, and talk late into the night again before a lazy Sunday morning and my departure.

During that time, we were both thinking a lot about what it means to be an artist, about life and death, and about what was next artistically, spiritually, and physically. We were having very existential conversations that transformed what could have been a singularly challenging experience into something much more profound and positive for both of us.

Exactly a year after I started supporting Tom through his cancer treatment and making this body of work, I was diagnosed with cancer. I was forced to relearn many lessons I thought I had learned while supporting Tom. I saw the work differently and ultimately decided it was important to incorporate some of that experience into the writing.

E: I know your background is in photojournalism, but you mention that this project shifted how you viewed yourself from a photojournalist/photographer to an artist. How has this shifted how you are working day-to-day?

D: As you say, I came into photography as a photojournalist, but I think, in many ways, that was because of the specific projects I was interested in. When I started, I focused on documenting traditional herding culture in Mongolia. In many ways, I got into photography through ethnomusicology more than anything else. As I was working in that methodology, it was really important not to insert my voice into the work. Of course, objectivity and truth in photography can be debated forever, but in general, I think great photojournalists are objective in trying to portray reality.

With this project, my initial goal was to document Tom’s journey. As I started making the work, it became clear that I wasn’t as interested in portraying reality. I became interested in representing what Tom and I were feeling. I started to think about capturing the emotional weight of the specific moment in time we were experiencing together.

I thought a lot about what I wanted to say with this work—my artistic voice. As a photojournalist, I believe it is important to push your opinions to the side in many instances, but as an artist, I don’t have to do that the same way.

In many ways, the more rigid structures I had placed on myself as a photojournalist helped me learn how to be a photographer, but they don’t serve me as much anymore. Going forward, I want to lean into that more emotive style of image-making, even if the story I’m trying to tell exists within photojournalism. I think there are ways to merge the two practices or lean into one or the other without doing something unethical.

E: Do you feel like this revision on how you label yourself/your work has shifted the topics you want to explore (ex., mortality, art making, etc)?

D: I confidently claim to be an artist now, which is something I would have never said before starting this project.

There are certain projects I am engaged in that will look and feel more photojournalistic and other projects that will feel much more like art. It’s okay to do both as long as I’m not deceiving the audience or hurting an individual or community in the image-making process.

I love that I’m interested in such different topics. At the moment, I’m working on a project about spirituality and wolf hunting in Mongolia. With that project in particular, I think it will be important to act as a photojournalist and be objective in how I represent a traditional culture. At the same time, I am excited to bring more artistically driven, emotive imagery into that work as I continue to explore the spiritual nature of the various practices I’m examining.

E: I am impressed by your ability to churn out personal projects. From “Heart-Shaped Tomatoes” to this current project. Can you tell us more about your process from development to implementation?

D: I laughed as I read this question because it really doesn’t feel like I’m churning anything out! It feels very slow.

Making my cookbook, “Heart-Shaped Tomatoes,” was a pivotal moment in my practice because it made me fall in love with the bookmaking process. At the moment, I see all the personal projects I’m working on as existing in book form. While that might not always be the case, I think for now, it helps me structure what the next steps are as I continue working on a project.

With “Close to the Bayou,” I didn’t originally envision creating a book. I was making pictures and seeing what would happen. Looking back at the images, I felt I was creating something very specific. There was something special going on, so I started printing out what I was capturing and sequencing the images. At the same time, I was trying to think about every memory of Tom that popped into my mind and writing it down with as much detail as I could remember. I would drive back and forth from Austin to Houston each weekend, so there was a lot of time to sit and think.

Certain themes started to repeat and pop out in the images and the writing, so I’d push myself in that direction or try to fill in what I saw was missing. Once Tom’s treatment was finished, I stopped making images and focused solely on pairing and sequencing the images and strengthening the text. I created two very different maquettes on my own before I got the book to where I felt like bringing on a designer was the necessary next step.

Shortly after I finished making the second maquette, I was diagnosed with cancer and had to go through surgery and chemotherapy. I was first considered cancer-free on May 5, 2022, and remain in remission. While I wasn’t focused on the book during that period, it was an important part of the creative process in many ways.

Over the last year and a half, I have worked with an incredible designer, Caleb Cain Marcus, to bring everything together. The concept and almost all the sequencing I brought to him is still the same, but he helped take everything to the next level to turn the book into the best version of itself.

In general, that’s how I see my process repeating over the next few years as I continue working on the projects I’m engaged in. It’s a process I enjoy, and I see myself only getting better at as I create more books.

Here’s a simplified version of my process:

Idea.

Making images.

Pairing and sequencing.

Make more images to fill out the story/body of work.

More pairing and sequencing.

Maquette

Repeat 4-6 as many times as necessary.

Bring on a designer.

Maquette with designer.

Raising money through presales.

Going to press.

As photographers, we often have to tell other people’s stories to make money. Stories for brands, restaurants, newspapers, etc. Personally, that’s not why I got into photography. While I still do all those things and genuinely enjoy doing them, my priority is my personal work, and I’ve been lucky to structure my life in a way that allows me to do that.

I think it’s important to articulate that, at least for now, that comes with certain sacrifices. I am not at a point in my career where I make a lot of money from my personal work, but I know that will change over time. Until that point, there are moments where I have to be very conscious about how I’m making and spending money.

I’m obsessed with making books and wouldn’t have it any other way!

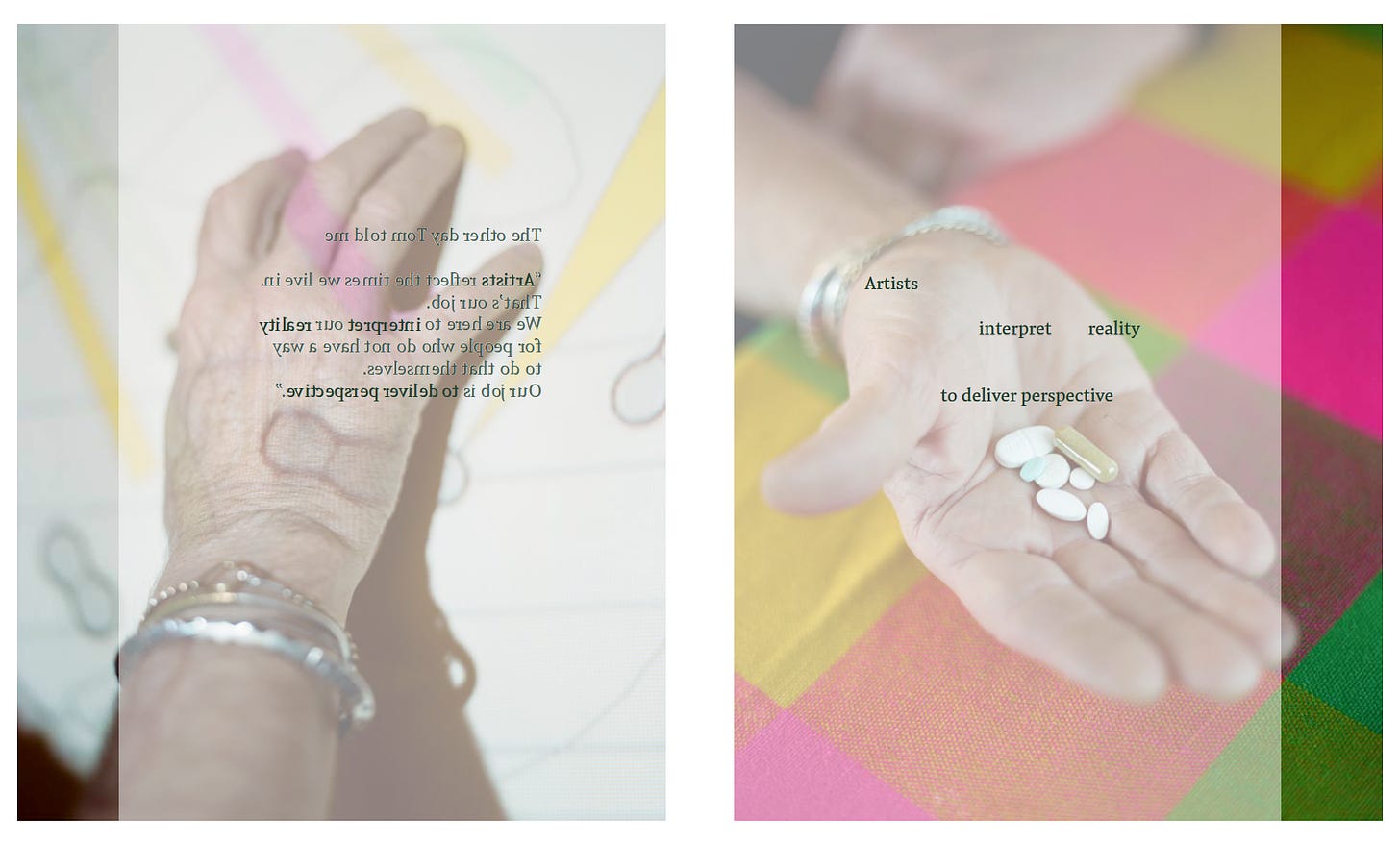

E: As I reviewed the book, the layering of the text on the (type of sheets?) offers factual information that morphs into the poetic as the layers of the text alter what the reader sees. Please tell us more about this idea and if there was a particular impact you were going for.

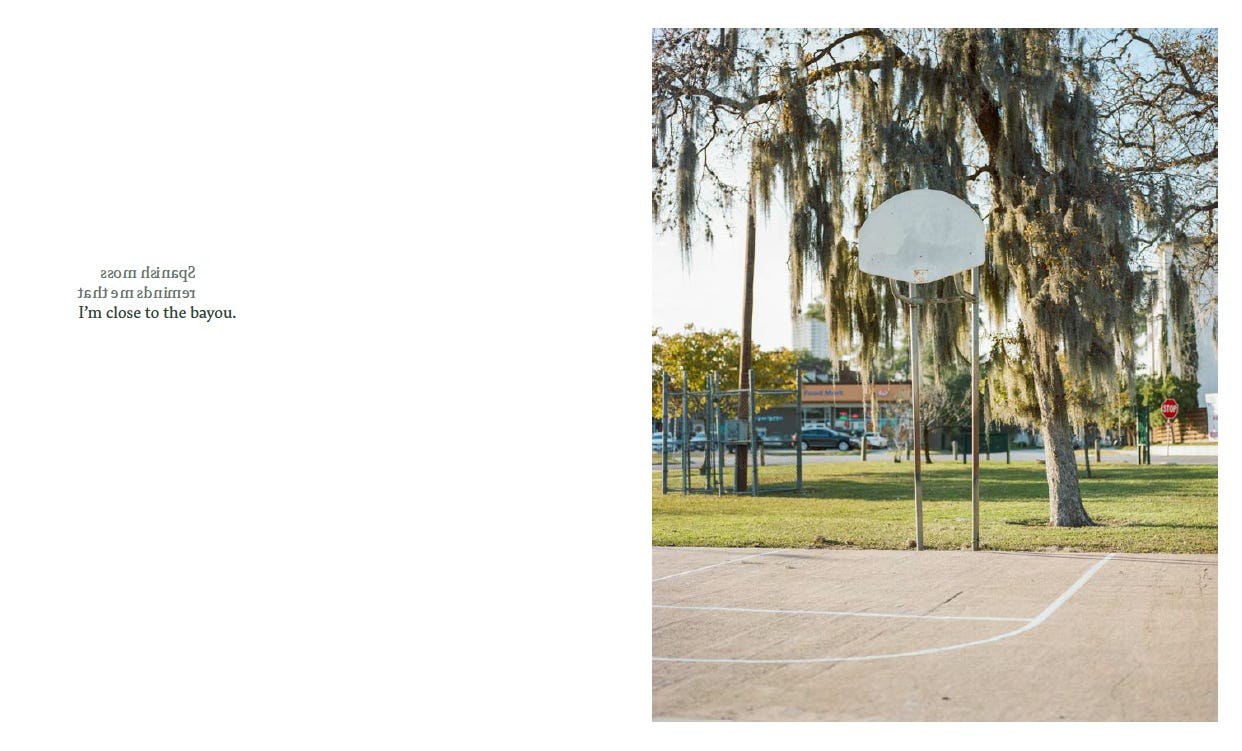

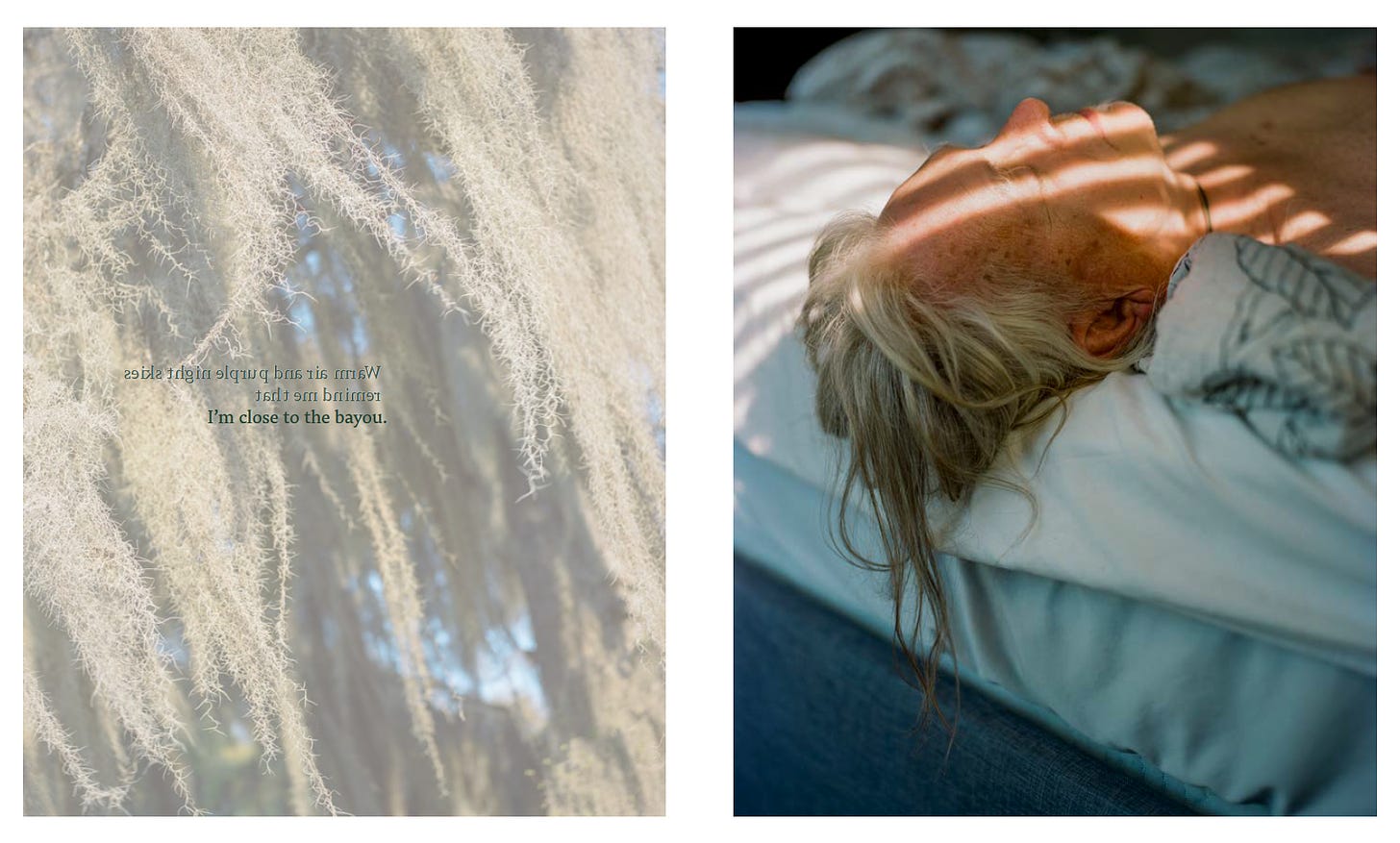

D: The idea behind using the translucent paper was to create an experience for the reader that mirrored what Tom and my experiences with cancer were like. Going through cancer treatment forces you to see yourself in different ways, to push through certain moments, to be held in a fog.

I was originally putting the text and imagery together on the same pages, but they detracted from each other. I had the idea to separate the images and text and never went back. Once I created a strong visual sequence with the photos, the text fell into place very naturally once I put them on the translucent sheets. They didn’t have to be directly related in the same way.

The tone of that paper feels like a bayou fog to me. The repeated phrase “close to the bayou” is a metaphor that I see as central to the work and that I hope readers connect with. Using a paper that strengthened that metaphor was important.

The translucent paper also allows the audience to have multiple experiences with the same image. That felt like a reflection of my own experience with cancer as I started to see someone I didn’t recognize in the mirror and as I lost my ability to think clearly. I know Tom had a similar experience as the drugs he was taking changed his body and mind.

It’s hard to tell on the PDF I sent you, but the translucent paper is something the reader will have to fight with a little bit. My goal is to allow the reader to have a physical exchange with the book. One in which they’re pushing sheets together or pulling them apart to read the text more clearly. Again, that was done to mirror the experience of cancer treatment.

Lastly, translucent tracing paper is something that Tom uses in his work as an artist, which is even referenced at one point in the book. Bringing that physical material into the book was interesting as it brought something from Tom’s reality into the book.

E: You are self-publishing this book and currently in the presale stage, correct? Can you offer insight or observations from your experience in self-publishing for artists/photographers/writers/etc, who are working on personal projects that may not have a place at a publisher or through an outlet?

D: I’m incredibly excited to work with a publisher for this project, which was not the case with my last book. Not everything has been finalized, but I’m excited to announce that partnership soon!

The expectation from almost all boutique photo book publishers is that the photographer is paying for the production of the book. Generally, the photographer is also paying the publisher to publish their book. If you want to work with a publisher, I think it’s essential to understand what they bring to the table. How will they elevate what you’ve spent so much time creating?

It has also been important for me to figure out the financial possibilities. With this book, my financial goal is to break even on the printing because of how high my per-book cost is. I was never making this book for the money. Still, I think it’s important to understand that reality if you want to make a super intricately designed book with multiple paper stocks, sheet lengths, an intricate cover design, etc. For my next book, I will think a lot more about the cost of each design decision I make.

I’m glad that my first book, “Heart-Shaped Tomatoes,” was self-published because it allowed me to control every aspect of the project. With that project, it was more important to me that my 101-year-old grandmother could see the final product than getting some big publisher to buy it. I’m very grateful that she was able to see it.

I’m excited to work with a publisher on this project, but I would have also been excited to self-publish. With photo books, self-publishing will always be cheaper because you don’t have to pay a publisher.

If someone is interested in making a book, I think it’s important to ask, “Why does this project need to be a book?”

As much as I LOVE books, I don’t think a book is always appropriate. There are certainly easier and cheaper ways to share your work. If you’re interested in making a book, I think it’s important to articulate why the specific project you’re working on will benefit from using the book form as the artistic medium. For “Heart-Shaped Tomatoes” and “Close to the Bayou,” I could easily articulate the why.

I have built a small but loyal following through my mailing list. That community has supported me over the years. The subscribed people have told me that they appreciate what I share with them because my newsletter always adds something of value to their day—I’m not just trying to sell books month after month.

A mailing list is a beneficial tool for artists making books because we own that information and can use it however we feel suits us best. Sharing your artistic journey authentically is something people are interested in. When the moment comes when you do need some support, the people who have been following along are excited to offer it.

E: Final question: What lesson have you learned from this process/project that you are taking into your creative practice?

D: As an artist and photographer, I look forward to incorporating a slower, more emotional type of image-making into my practice.

As a human, I’m grateful that I said yes to supporting Tom because it allowed us to reach a level in our friendship that I never could have imagined. That friendship has added a lot of meaning to my life and has made me a better person.

Tom allowed me to give myself permission to see myself as an artist.

You can learn more about supporting the project by going to this website. You can follow Dimitri on Instagram and see his portfolio here.

In 2023, Argo Collective (the photography collective I am a member of) produced “In Plain Sight,” our first collaborative project. The images throughout the zine examine the familiar presence of the American flag in a myriad of forms and locations throughout the nation.

If you want a copy, follow this link and fill out the form, and I’ll send you a copy. This link will be active until I run out of copies.

Below, you can see a flip-through of the zine.

That’s all for the first edition of 2024. If you or a friend are working on a long-term project and would like to share it with followers of The Practice, please reach out!

I’ll return next week with a rundown of my creative portrait session at the end of 2023.